This is the History of Social Work. Most of these figures were probably not taught about or even mentioned in a social work class. Oftentimes we hear about the same people but there is more to Social Work than the one’s claimed to have started it all like Jane Addams and Mary Richmond. Some do not hold the official “social work” title but embody the very essence of the field. However they do include BIPOC, queer, disabled, and many other marginalized populations. Knowledge is power and representation matters. This is the history of social work.

Bernice Catherine Harper (1925 – )

Activist, Writer, Social Worker

Dr. Bernice Catherine Harper was Medical Care Advisor to the Health Care Financing Administration in Washington, D.C. Her career, which has progressed to this most influential federal level, has focused on the area of health care and health care policy formulation.

Read MoreShe has practiced in varied settings and personified the values and ethical standards of the social work profession even in the most difficult and highly charged political environments. Harper earned her MSW Degree from the University of Southern California in 1948, her MSc.PH from Harvard University in 1959, and her LLD Degree from Faith Grant College, Birmingham, Alabama.

She was instrumental in developing long-term program policies, which highlight continuity-of-care, including community, and institutional care, and stresses the importance of psychosocial components. Her commitment to the long-term care of those in need has served to demonstrate the best of the best for the profession and for those in need. Her insight and commitment to professionals, especially social workers, who are under both personal and professional stress as they work with patients in the final phases of their lives, combined with her perspective, academic, and practice skills with their families, motivated her to produce a definitive publication on death and the special needs for professionals to cope with their related stress. The book, Death: The Coping Mechanism of the Health Professional, was in advance of the interest now placed on this area. Harper identified and labeled specific stages of coping with death that are important to understand, especially for professionals living through the process with clients.

Harper’s work at the City of Hope in California, as Chief Social Worker, and her practice with leukemia patients and families sustained her interest in the important needs of those with chronic and long- term illness. She is nationally-recognized for her work and is sought after for training workshops and conferences. Bernice Harper has consistently been referred to as the professional’s professional. She has been able to represent social work values and bring them into policy statements. She is a personification of social work’s value base and has sustained that consistency in the Washington scene through multiple and changing administrations as well as political appointees. She has not compromised the long-term health care needs of those in the country. She also has worked with multiple government organizations around minority services and activities for professional as well as other educational needs.

Harper serves on the Board of Directors for the NASW Foundation and has been active and held leadership positions at NASW and the International Conference on Social Welfare. She was the first recipient of the NASW Foundation’s Knee/Wittman Outstanding Achievement in Health/Mental Health Policy Award. In 2017, Harper was inducted into the California Social Work Hall of Distinction.

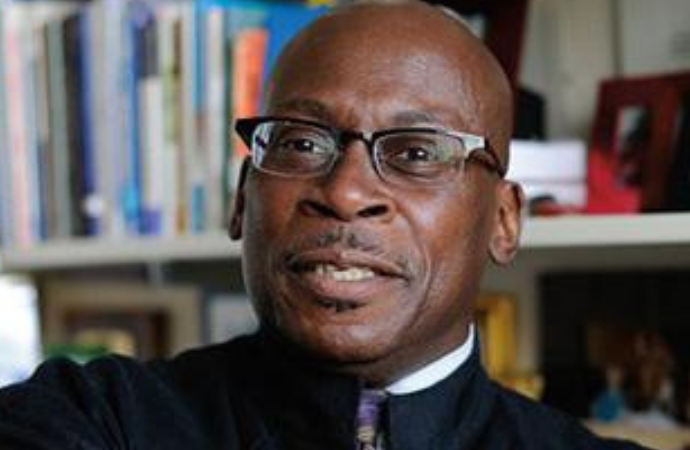

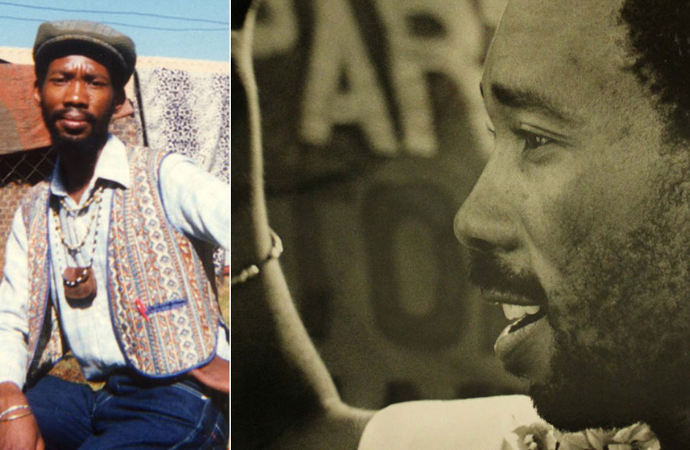

Gary Bailey (~ 1955 – )

Social Worker

Gary Bailey, MSW, ACSW, is a native of Cleveland, Ohio. He received his BA from the Eliot Pearson School of Child Study at Tufts University in 1977 and his MSW from Boston University School of Social Work in 1979. He is currently an Associate Professor at Simmons College Graduate School of Social Work where he chairs the Dynamics of Racism and Oppression foundation sequence.

Read MoreHe is a member of the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE) I Hartford Foundation Gero Education Initiative to infuse gerontological content into curriculum. Professor Bailey is the Chair of the Simmons College Black Administrators, Faculty and Staff Council (BAFAS); and Chairs the School of Social Work (SSW) Awards committee. He is a member of the President’s Inaugural Committee.

He holds an appointment as an adjunct Assistant Professor at the Boston University School of Public Health. Professor Bailey is currently the Chairperson of the National Social Work Public Education Campaign and he is a member of the NASW Foundation Board of Directors.

He was the President of NASW from 2003 until 2005. He was the President-elect from 2002-2003. His tenure at NASW National has included serving as the NASW National 2nd Vice President 2000-2002 and as the Association’s Treasurer from 1995-1997. He was a member or the NASW Insurance Trust Board of Trustees. He was the President of the Massachusetts Chapter of NASW from 1993-1995.

Professor Bailey is a past president of the North American Region of the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) Berne, Switzerland having served in that role from 2003 until 2006. He was elected Chair of the Policy, Advocacy and Representation Commission in August 2006 at the IFSW Executive Committee meeting in Munich Germany. He is also a member of the IFSW Task Force on Fees. He is a member of the board of the North American and Caribbean Association of Schools of Social Work representing the Council of Social Work Education (CSWE).

Professor Bailey is the recipient of numerous awards and honors. He was named Social Worker of the Year by both the National and Massachusetts NASW in 1998. He was made a Social Work Pioneer (www.naswfoundation.org/pioneer) by NASW in 2005, making him the youngest individual to receive this honor, joining individuals such as Jane Adams, Whitney M. Young, and Simmons own Dr. Helen Reinherz.

Professor Bailey received the Boston University School of Social Work Alumni Association Award for Outstanding Contributions to the Field of Social Work in 1995. He received the Wayne S Wright Advocacy Award from the Multicultural AIDS Coalition in 1997; the Congressman Gerry Studds Visibility A ward in 1996, and the Bayard Rustin Spirit Award from the AIDS Action Committee of Massachusetts in 1999. He was recognized with an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree from the University of Connecticut in 2013.

He has served on numerous Boards and Advisory groups including the Advisory committees for the Massachusetts Departments of Mental Health and Social Services. He chaired the AIDS Action Committee of Boston Board of Directors and was co-chair of the Children’s Hospital Community Advisory Committee. He was a member of the boards of directors at the Phillip Brooks House at Harvard University, the Massachusetts Maternity and Foundling Hospital Foundation, United Homes for Children, the Wang Center for the Performing Arts, and the Center for Family Connections.

He began his career at Family Service of Greater Boston in 1980 working in Services for Older People by providing casework and other services to at-risk elders and their families. He went on to hold numerous positions at Family Service until he left in 1994 to assume the position of Executive Director of Parents and Children’s Services in Boston.

Professor Bailey is highly sought after as a trainer and consultant on topics which include board development; international social work practice; elder and family housing program development; issues pertaining to diversity, social justice and human rights; and working with gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) communities. He and his partner Richard McCarthy and their Cairn Terrier, Budd divide their time between their homes in Boston and Provincetown, Massachusetts.

Thyra J. Edwards (1897-1953)

Educator, Social Worker, Journalist, Activist, Labor Organizer

Thyra J. Edwards, born in 1897, the granddaugher of runaway slaves, grew up in Houston, Texas and started her career there as a school teacher. Eventually she moved to Gary, Indiana and later Chicago where she was trained in social work at the Chicago School of Civics and Philanthropy, Edwards pursued her interest in child welfare through a variety of social work positions that showcased her work with children, which gave way to the founding of her own children’s home. Read More

Also keenly interested in labor relations, Edwards studied labor management issues at Brockwood Labor College in New Jersey. Later, she was employed as a social worker. Edwards would eventually become a world lecturer, journalist, labor organizer, women’s rights advocate, and civil rights activist all before her 40th birthday.

By 1944 Edwards was heralded as “one of the most outstanding Negro women in the world.” She had an international approach to social work and viewed her journalistic work, travel seminars, speaking engagements, and union organizing as a part of her role as a professional in the social work arena. By the end of World War II she was the executive director of the Congress of American Women.

Concerned foremost with the plight of women and children, in 1953 Edwards organized the first Jewish child care program in Rome to assist children who had been victims of the Holocaust. From her point of view social work should: advocate for disadvantaged and at-risk populations; focus on issues and problems specifically affecting the well-being of women; and demonstrate the ability to work with diverse populations. Her views are akin to many principles currently articulated by the Council of Social Work Education. Her work was grounded in what modern sociologists call “work systems theory.”

The link between the plight of Blacks throughout the world was a cornerstone of her professional philosophy. At a time when the social work profession in the United States believed that Black social workers should only focus on Blacks in America, Edwards worked with people of all races, nationalities, and ethnicities.

It was that viewpoint that attracted her to the Communist Party while she was living in New York in the 1930s, Edwards publicly supported the Loyalists in the Spanish Civil War and used her role as a correspondent to travel to Europe, Mexico, and the Soviet Union. Her activities with the U.S. Communists drew the attention of the FBI and she was monitored by U.S. government intelligence organizations until her death. Thyra Edwards died in 1953 at the age of 55.

Norma Gray “Cindy” Jones (1951-2017)

Social Worker, Military Officer

Norma Gray Jones was the US Navy’s first African American female social work officer. She served for 21 years as a Navy Commander where her work altered Navy social practices and policies. Her efforts included establishing new programs for entry-level Navy social workers and implementing Family Advocacy treatment programs worldwide.

She held several program management positions to include, Deputy Directory Fleet and Family Support Programs and the Director of Research for the Fleet and Family Support Programs in Millington, TN. She established new billets for Navy social workers in Diego Garcia, and Bahrain. Jones served as Director of Behavioral Health Services at the Naval Hospital, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, focusing primarily on the “Children Soldiers” population and assisting political prisoners and refugees. Her last position on active duty was, Director of Social Work Department at the Naval Medical Center in Portsmouth, VA. Jones began her military career in San Diego, CA and was then transferred to Adak, Alaska as part of a two-person mental health team, working with military families and family violence issues. The WIC program she established there was used until the base closing in 1996. Jones served as Regional Family Advocacy Representative in London, England, served five major naval bases, and established a position for a naval psychiatrist in the UK, which was a first. She also served as a consultant and trainer to the US Embassies in London and Paris on matters related to family violence.

Fannie Lou Hamer (1917-1977)

Activist, Community Organizer

Fannie Lou Townsend Hamer rose from humble beginnings in the Mississippi Delta to become one of the most important, passionate, and powerful voices of the civil and voting rights movements and a leader in the efforts for greater economic opportunities for African Americans.

Read MoreHamer was born on October 6, 1917 in Montgomery County, Mississippi, the 20th and last child of sharecroppers Lou Ella and James Townsend. She grew up in poverty, and at age six Hamer joined her family picking cotton. By age 12, she left school to work. In 1944, she married Perry Hamer and the couple toiled on the Mississippi plantation owned by B.D. Marlowe until 1962. Because Hamer was the only worker who could read and write, she also served as plantation timekeeper.

That summer, Hamer attended a meeting led by civil rights activists James Forman of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and James Bevel of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Hamer was incensed by efforts to deny Blacks the right to vote. She became a SNCC organizer and on August 31, 1962 led 17 volunteers to register to vote at the Indianola, Mississippi Courthouse. Denied the right to vote due to an unfair literacy test, the group was harassed on their way home, when police stopped their bus and fined them $100 for the trumped-up charge that the bus was too yellow. That night, Marlow fired Hamer for her attempt to vote; her husband was required to stay until the harvest. Marlow confiscated much of their property. The Hamers moved to Ruleville, Mississippi in Sunflower County with very little.

In June 1963, after successfully completing a voter registration program in Charleston, South Carolina, Hamer and several other Black women were arrested for sitting in a “whites-only” bus station restaurant in Winona, Mississippi. At the Winona jailhouse, she and several of the women were brutally beaten, leaving Hamer with lifelong injuries from a blood clot in her eye, kidney damage, and leg damage.

In 1964, Hamer’s national reputation soared as she co-founded the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), which challenged the local Democratic Party’s efforts to block Black participation. Hamer and other MFDP members went to the Democratic National Convention that year, arguing to be recognized as the official delegation. When Hamer spoke before the Credentials Committee, calling for mandatory integrated state delegations, President Lyndon Johnson held a televised press conference so she would not get any television airtime. But her speech, with its poignant descriptions of racial prejudice in the South, was televised later. By 1968, Hamer’s vision for racial parity in delegations had become a reality and Hamer was a member of Mississippi’s first integrated delegation.

In 1964 Hamer helped organize Freedom Summer, which brought hundreds of college students, Black and white, to help with African American voter registration in the segregated South. In 1964, she announced her candidacy for the Mississippi House of Representatives but was barred from the ballot. A year later, Hamer, Victoria Gray, and Annie Devine became the first Black women to stand in the U.S. Congress when they unsuccessfully protested the Mississippi House election of 1964. She also traveled extensively, giving powerful speeches on behalf of civil rights. In 1971, Hamer helped to found the National Women’s Political Caucus.

Frustrated by the political process, Hamer turned to economics as a strategy for greater racial equality. In 1968, she began a “pig bank” to provide free pigs for Black farmers to breed, raise, and slaughter. A year later she launched the Freedom Farm Cooperative (FFC), buying up land that Blacks could own and farm collectively. With the assistance of donors (including famed singer Harry Belafonte), she purchased 640 acres and launched a coop store, boutique, and sewing enterprise. She single-handedly ensured that 200 units of low-income housing were built—many still exist in Ruleville today. The FFC lasted until the mid-1970s; at its heyday, it was among the largest employers in Sunflower County. Extensive travel and fundraising took Hamer away from the day-to-day operations, as did her failing health, and the FFC hobbled along until folding. Not long after, in 1977, Hamer died of breast cancer at age 59.

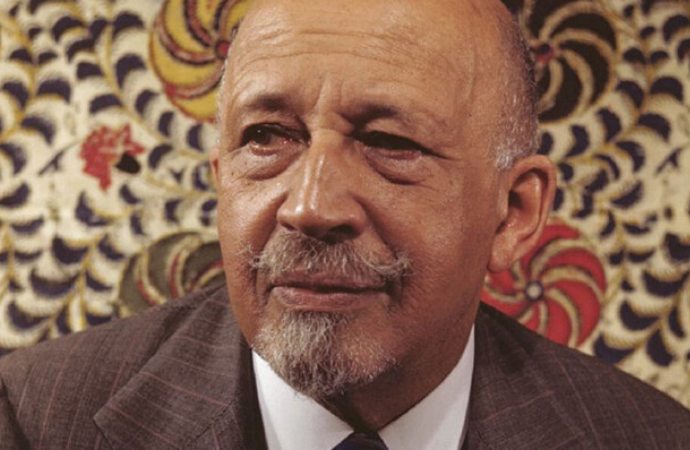

Whitney M. Young Jr. (1921-1971)

Activist, Presidential Advisor, Social Worker

Whitney Young was an American civil rights leader. He spent most of his career working to end employment discrimination in the United States and turning the National Urban League from a relatively passive civil rights organization into one that aggressively worked for equitable access to socioeconomic opportunity for the historically disenfranchised.

Read MoreAfter earning his social work master’s from the University of Minnesota, he went on to work for The Urban League. The Urban League had traditionally been a cautious and moderate organization with many white members. During Young’s ten-year tenure at the League, he brought the organization to the forefront of the American Civil Rights Movement. He both greatly expanded its mission and kept the support of influential white business and political leaders. A noted civil rights leader and statesman, he worked to eradicate discrimination against blacks and poor people. He served on numerous national boards and advisory committees and received many honorary degrees and awards —including the Medal of Freedom (1969), presented by President Lyndon Johnson—for his outstanding civil rights accomplishments. Despite his reluctance to enter politics himself, Young was an important advisor to Presidents Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon.

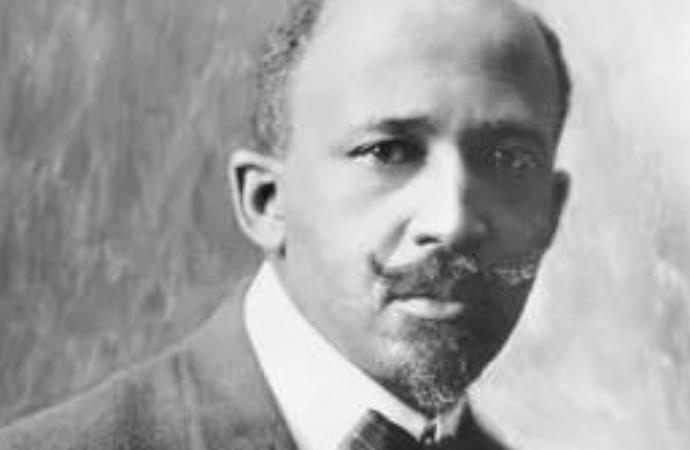

W.E.B Du Bois (1868–1963)

Activist, Journalist, Historian, Sociologist, Novelist, Philosopher

Before becoming a founding member of NAACP, W.E.B. Du Bois was already well known as one of the foremost Black intellectuals of his era. The first Black American to earn a PhD from Harvard University, Du Bois published widely before becoming NAACP’s director of publicity and research and starting the organization’s official journal, The Crisis, in 1910.

Read MoreDu Bois, a scholar at the historically Black Atlanta University, established himself as a leading thinker on race and the plight of Black Americans. He challenged the position held by Booker T. Washington, another contemporary prominent intellectual, that Southern Blacks should compromise their basic rights in exchange for education and legal justice. He also spoke out against the notion popularized by abolitionist Frederick Douglass that Black Americans should integrate with white society. In an essay published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1897, “Strivings of the Negro People,” Du Bois wrote that Black Americans should instead embrace their African heritage even as they worked and lived in the United States.

Du Bois published his seminal work The Souls of Black Folk in 1903. In this collection of essays, Du Bois described the predicament of Black Americans as one of “double consciousness”: “One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, who dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” The term “double consciousness” has come to be widely used as a theoretical framework to apply to other dynamics of inequality.

When looking at his beginning work with the NAACP, it is clear he made meaningful contributions. Du Bois became the editor of the organization’s monthly magazine, The Crisis, using his perch to draw attention to the still widespread practice of lynching, pushing for nationwide legislation that would outlaw the cruel extrajudicial killings. A 1915 article in the journal gave a year-by-year list of more than 2,700 lynchings over the previous three decades.

Du Bois, who considered himself a socialist, also published articles in favor of unionized labor, although he called out union leaders for barring Black membership. Under Du Bois’s guidance, the journal attracted a wide readership, reaching 100,000 in 1920, and drew many new supporters to NAACP. With Du Bois as its mouthpiece, NAACP came to be known as the leading protest organization for Black Americans.

“One ever feels his twoness, — an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, who dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Du Bois served as editor of The Crisis until 1934, when he resigned following a rift with NAACP leadership over his controversial stance on segregation. He viewed the “separate but equal” status as an acceptable position for Blacks. Du Bois also resigned from the NAACP board and returned to Atlanta University.

After a ten-year hiatus, Du Bois came back to NAACP as the director of special research from 1944 to 1948. In this role, he attended the founding convention for the United Nations, channeling his energies toward lobbying the global body to acknowledge the suffering of Black Americans. He wrote the famous NAACP publication, “An Appeal to the World,” a precursor to a report charging the United States with genocide for its ugly history of state-sanctioned lynchings. Du Bois also turned a spotlight onto the injustices of colonialism, urging the United Nations to use its influence to take a stand against such exploitative regimes.

Throughout his life, Du Bois was active in the Pan-Africanism movement, attending the First Pan-African Conference in London in 1900. He later organized a series of Pan-African Congress meetings around the world in 1919, 1921, 1923, and 1927, bringing together intellectuals from Africa, the West Indies, and the United States.

At the end of his life, Du Bois embarked on an ambitious project to create a new encyclopedia on the African diaspora, funded by the government of Ghana. A citizen of the world until the end, the 93-year-old Du Bois moved to Ghana to manage the project, acquiring citizenship of the African country in 1961. Du Bois died in Ghana on Aug. 27, 1963, the day before the historic March on Washington.

Herman George Canady (1901-1970)

Psychologist

Herman George Canady was a prominent Black clinical and social psychologist. He is credited with being the first psychologist to study the influence of rapport between an IQ test proctor and the subject, specifically researching how the race of a test proctor can create bias in IQ testing. He also helped to provide an understanding of testing environments that were suitable to help Black students succeed.

Carrie Steele Logan (1829-1900)

Activist

Mrs. Carrie Steele, worked as a maid at the Union Railroad Station in downtown Atlanta in the late 1800s when she discovered that abandoned babies and children were being left at the station. She began to care for these children, placing them in an empty boxcar during the day and taking them home with her at night. In 1888, Mrs. Steele chartered an organization, eventually selling her home and generating additional funds from the community to build the first facility called the “Carrie Steele Orphan Home”.

Alice Walker (1944- )

Author, Social Worker

Pulitzer Prize-winning author Alice Walker pursued her higher education in social work at Sarah Lawrence College. After graduating in 1965, she moved to Mississippi to join the Civil Rights Movement and welfare rights campaigns. Walker continued working in the civil rights movement while teaching at various universities.

Read MoreDuring this time she also became a major voice in the emerging feminist movement led by mostly white middle-class women Her writing career took off after becoming an editor for Ms. magazine. In 1982, Alice Walker published her best-known novel, The Color Purple, which was famously adapted onto film by Steven Spielberg.

Ida B. Wells (1862-1931)

Activist, Investigative Journalists, Educator, Researcher

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was a prominent journalist, activist, and researcher, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In her lifetime, she battled sexism, racism, and violence. As a skilled writer, Wells-Barnett also used her skills as a journalist to shed light on the conditions of African Americans throughout the South.

Read MoreIda Bell Wells was born into slavery during the Civil War. Once the war ended Wells-Barnett’s parents became politically active in Reconstruction Era politics and instilled into Wells the importance of education. Wells-Barnett enrolled at Rust College but was expelled when she started a dispute with the university president. In 1878, Wells-Barnett was informed that a yellow fever epidemic had hit her hometown. The disease took both of Wells-Barnett’s parents and her infant brother. Left to raise her brothers and sister, she took a job as a teacher so that she could keep the family together.

However, after the lynching of one of her friends, Wells-Barnett turned her attention to white mob violence. She became skeptical about the reasons black men were lynched and set out to investigate several cases. She published her findings in a pamphlet and wrote several columns in local newspapers. She exposed about an 1892 lynching enraged locals, who burned her press and drove her from Memphis. After a few months, the threats became so bad she was forced to move to Chicago, Illinois.

In 1893, Wells-Barnett, joined other African American leaders in calling for the boycott of the World’s Columbian Exposition. The boycotters accused the exposition committee of locking out African Americans and negatively portraying the black community. In 1895, Wells-Barnett married famed African American lawyer Ferdinand Barnett. Together, the couple had four children.

Wells-Barnett traveled internationally, shedding light on lynching to foreign audiences. Abroad, she openly confronted white women in the suffrage movement who ignored lynching. Because of her stance, she was often ridiculed and ostracized by women’s suffrage organizations in the United States. Nevertheless, Wells-Barnett remained active the women’s rights movement. She was a founder of the National Association of Colored Women’s Club which was created to address issues dealing with civil rights and women’s suffrage. Although she was in Niagara Falls for the founding of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), her name is not mentioned as an official founder. Late in her career Wells-Barnett focused on urban reform in the growing city of Chicago. She died on March 25th, 1931.

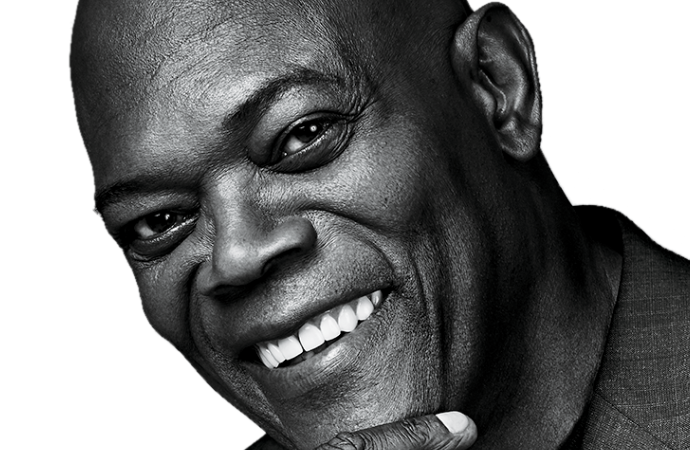

Samuel L. Jackson (1948- )

Social Worker, Actor

Before becoming a critically acclaimed actor, Samuel L. Jackson attended Atlanta’s Morehouse College and majored in social work. While attending Morehouse College in Atlanta in 1969, he protested the lack of black members on the board of trustees. He was expelled from the college for his protest (which involved locking trustees into a building!) and later returned to pursue acting after working for two years as a social worker in Los Angeles.

He joined the Civil Rights Movement to advocate for Black Power and equal rights. By 1972, he made his feature film debut in Together for Days. Now, Samuel L. Jackson has a total box office gross of over $4.6 million from movies like Pulp Fiction and The Negotiator. Now he’s won multiple NAACP Image Awards, Golden Globes, and is an acclaimed actor and director.

Mary Church Terrell (1863-1954)

Activist

Mary Eliza Church Terrell was a well-known African American activist who championed racial equality and women’s suffrage in the late 19th and early 20th century. An Oberlin College graduate, Terrell was part of the rising black middle and upper class who used their position to fight racial discrimination.

Read MoreThe daughter of former slaves, Terrell was born on September 23, 1863 in Memphis, Tennessee. Her father, Robert Reed Church, was a successful businessman who became one of the South’s first African American millionaires. Her mother, Louisa Ayres Church, owned a hair salon. She had one brother. Their affluence and belief in the importance of education enabled Terrell to attend the Antioch College laboratory school in Ohio, and later Oberlin College, where she earned both Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees. Terrell spent two years teaching at Wilburforce College before moving to Washington DC, in 1887 to teach at the M Street Colored High School. There she met, and in 1891, married Heberton Terrell, also a teacher. The Terrells had one daughter and later adopted a second daughter.

Her activism was sparked in 1892, when an old friend, Thomas Moss, was lynched in Memphis by whites because his business competed with theirs. Terrell joined Ida B. Wells-Barnett in anti-lynching campaigns, but Terrell’s life work focused on the notion of racial uplift, the belief that blacks would help end racial discrimination by advancing themselves and other members of the race through education, work, and community activism. It was a strategy based on the power of equal opportunities to advance the race and her belief that as one succeeds, the whole race would be elevated. Her words—“Lifting as we climb”—became the motto of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), the group she helped found in 1896. She was NACW president from 1896 to 1901.

As NACW president, Terrell campaigned tirelessly among black organizations and mainstream white organizations, writing and speaking extensively. She also actively embraced women’s suffrage, which she saw as essential to elevating the status of black women, and consequently, the entire race. She actively campaigned for black women’s suffrage. She even picketed the Wilson White House with members of the National Woman’s Party in her zeal for woman suffrage. Terrell fought for woman suffrage and civil rights because she realized that she belonged “to the only group in this country that has two such huge obstacles to surmount…both sex and race.”

In 1909, Terrell was among the founders and charter members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Then in 1910, she co-founded the College Alumnae Club, later renamed the National Association of University Women.

Following the passage of the 19th amendment, Terrell focused on broader civil rights. In 1940, she published her autobiography, A Colored Woman in a White World, outlining her experiences with discrimination. In 1948, Terrell became the first black member of the American Association of University Women, after winning an anti-discrimination lawsuit. In 1950, at age 86, she challenged segregation in public places by protesting the John R. Thompson Restaurant in Washington, DC. She was victorious when, in 1953, the Supreme Court ruled that segregated eating facilities were unconstitutional, a major breakthrough in the civil rights movement. Terrell died four years later in Highland Beach, Maryland.

Dorothy Height (1912-2010)

Activist, Community Organizer, Psychologist, Social Worker

Dorothy Irene Height was born on March 24th, 1912 in Richmond, Virginia. Her family later moved to Rankin, Pennsylvania where she excelled as a student. Height eventually received a scholarship to attend college. In 1929, she was admitted to Barnard College but was not allowed to attend because the school did not admit African Americans. Read More

Instead, Height went on to graduate from New York University where she received a bachelor’s in education and master’s in psychology. Her first job was as a social worker in Harlem, New York. She later joined the staff of the Harlem Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). In no time, Height became a leader in the local organization. She created diverse programs and pushed the organization to integrate YWCA facilities nationwide.

During a chance encounter with African American leader Mary McLeod Bethune, Height was inspired to begin working with the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW). Through the NCNW, Height focused on ending the lynching of African Americans and restructuring the criminal justice system. In 1957, she became the fourth president of the NCNW. Under her leadership, the NCNW supported voter registration in the South. The NCNW also financially aided several civil rights activists throughout the country. Height was president of NCNW for 40 years.

Height’s prominence in the Civil Rights Movement and unmatched knowledge in organizing, meant she was regularly called to give advice on political issues. Eleanor Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Lyndon B. Johnson often sought her counsel. In 1963, Height, along with other civil rights activists organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Although she played a role in the march, she was not invited to speak. In fact, originally no women were included on the program at all. Height and Anna Arnold Hedgeman persuaded the other organizers to allow a woman to speak. Despite the apparent gender discrimination in the Civil Rights Movement, Height continued working on the front lines.

In addition to her work in the United States, Height traveled extensively. She served as a visiting professor at the University of Delhi, India and with the Black Women’s Federation of South Africa. For all her efforts during the Civil Rights Movement, Height was awarded and recognized by many organizations. In 1989, she received the Citizens Medal Award from President Ronald Reagan and in 2004, Height was honored with the Congressional Gold Medal. The same year, Height was inducted into the Democracy Hall of Fame International. She also received an estimated 24 honorary degrees. On April 20th, 2010, Height passed away at the age of 98. Her funeral was held at Washington National Cathedral.

Dr Charles R Drew (1904-1950)

Innovative Humanitarian, Surgeon, Researcher

Charles Richard Drew, the African American surgeon and researcher who organized America’s first large-scale blood bank and trained a generation of black physicians at Howard University, was born in Washington, DC, on June 3, 1904. His upbringing emphasized academic education and church membership, as well as civic knowledge and personal competence, responsibility, and independence.

Read MoreWashington was still racially segregated during that era, but its large African American community included many prosperous and well-educated families, and their public schools were often excellent. Drew attended Stevens Elementary and then Dunbar High School, which was then one of the best college preparatory schools–for blacks or whites–in the country. Though bright, he was not an outstanding student; instead, he devoted much of his effort to athletics, where he excelled.

Drew graduated from Dunbar in 1922 and went to Amherst College in Massachusetts on an athletic scholarship. His achievements on the Amherst track and football teams were legendary; long after he distinguished himself as a blood banking pioneer and medical educator, many still remembered him best as an athlete. Drew received his AB from Amherst in 1926. To earn money for medical school, he took a job as athletic director and instructor of biology and chemistry at Morgan College (now Morgan State University), in Baltimore. During his two years at Morgan, his coaching transformed its mediocre sports teams into serious collegiate competitors.

The racial segregation of the pre-Civil Rights era constrained Drew’s options for medical training. Some prominent medical schools, such as Harvard, accepted a few non-white students each year, but most African Americans aspiring to medical careers trained at black institutions such as the Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, DC, or Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. Drew applied to Howard, but was not accepted because he lacked enough credits in English from Amherst. Harvard accepted him, but wanted to defer his admission to the following year. Not wanting to wait, Drew applied to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine in Montréal, which had a reputation for better treatment of minorities.

McGill University allowed its graduate and professional students to play on school teams, and Drew once again became a star athlete. But he also became a star student, winning several important prizes and fellowships, and graduating second in a class of 137, in 1933. During his internship and surgical residency at Montréal General Hospital, 1933-1935, he worked closely with bacteriology professor John Beattie, who was exploring ways to treat shock with transfusion and other fluid replacement. This work fostered an interest in transfusion medicine that Drew would later pursue in his blood bank research. Drew hoped to extend his training with a surgical residency in the United States, preferably at the Mayo Clinic, but major American medical centers rarely took on African American residents, partly because many white patients in that era would refuse to be treated by black physicians. In 1935, he joined the faculty at Howard University College of Medicine, starting as a pathology instructor, and then progressing to surgical instructor and to chief surgical resident at Freedmen’s Hospital.

Howard’s College of Medicine was upgrading its programs with help from the Rockefeller Foundation’s General Education Board. This effort included appointing well-qualified white department chairs to set up and run residency programs and train black successors, along with fellowships for further training of junior faculty. Drew trained with Department of Surgery chair Edward Lee Howes for three years and then got a fellowship to train with eminent surgeon Allen O. Whipple at New York’s Presbyterian Hospital, while earning a doctorate in medical science from Columbia University. At Presbyterian, he worked with John Scudder on studies relating to treating shock, fluid balance, blood chemistry and preservation, and transfusion. His main project with Scudder–and the basis for his dissertation–was an experimental blood bank at Presbyterian, opened in August 1939. In June 1940, Drew received his doctorate in medical science from Columbia, becoming the first African American to earn the degree there.

With his fellowship completed, Drew returned to Howard University to take up duties as assistant professor of surgery. He was called back to New York in September 1940 to direct the Blood for Britain project. Great Britain, then under attack by Germany, was in desperate need of blood and plasma to treat military and civilian casualties. In August, Presbyterian and five other New York hospitals had begun a collaborative effort to collect and ship plasma (the fluid, non-cellular portion of blood) to Britain. Although others had developed the basic methods for plasma use, Drew, as medical director, instituted uniform procedures and standards for collecting blood and processing blood plasma at the participating hospitals. When the program ended in January 1941, Drew was appointed assistant director of a pilot program for a national blood banking system, jointly sponsored by the National Research Council and the American Red Cross. Among his innovations were mobile blood donation stations, later called “bloodmobiles.” Ironically, as the blood bank effort expanded in preparation for America’s entry into the war, the armed forces initially stipulated that the Red Cross exclude African Americans from donating; thus Drew, a leading expert in blood banking, was ineligible to participate in the program he helped establish. The policy was soon modified to accept blood donations from blacks, but required that these be segregated. Throughout the war, Drew criticized these policies as unscientific and insulting to African Americans.

While working on the Blood for Britain project, Drew also passed his American Board of Surgery exams, receiving certification early in 1941. He returned to Howard University and in October became chair of the Department of Surgery and Chief of Surgery at Freedmen’s Hospital. He also became the first African American to be appointed an examiner for the American Board of Surgery. For the next nine years he devoted himself to training and mentoring his medical students and surgical residents, and raising standards in black medical education. He also campaigned against the exclusion of black physicians from local medical societies, medical specialty organizations, and the American Medical Association.

Drew’s innovative work was recognized by awards and honors including the 1942 E. S. Jones Award for Research in Medical Science from the John A. Andrew Clinic in Tuskegee, AL; an appointment to the American-Soviet Committee on Science in 1943; the 1944 Spingarn Medal from the NAACP, for his work on blood and plasma; honorary doctorates from Virginia State College (1945) and Amherst College (1947); and election to the International College of Surgeons in 1946.

Drew died on April 1, 1950, in Burlington, North Carolina, from injuries sustained in a car accident while en route to a conference. Despite the prompt and competent care he received from the white physicians at a nearby hospital, he was too badly injured to survive. Drew’s tragic death generated a persistent myth that he died because he was denied admission to the white hospital, or was denied a transfusion, but such stories have been debunked repeatedly. Though he died prematurely, Drew left a substantial legacy, embodied in his blood bank work and especially in the graduates of the Howard University College of Medicine.

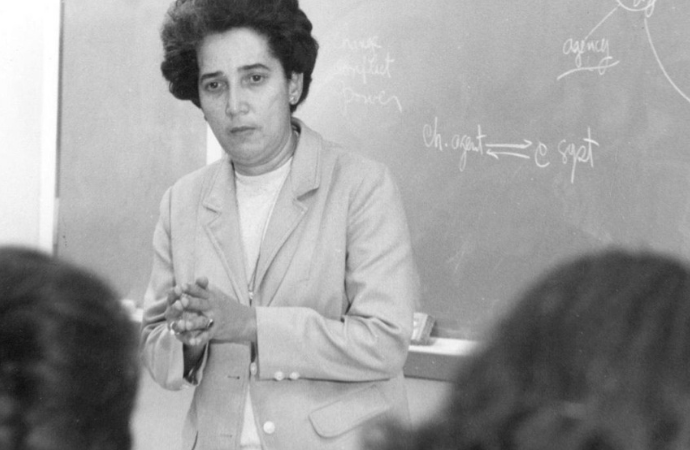

Angela Davis (1944- )

Activist, Educator, Author

A black militant American activist, Davis studied at home and abroad (1961–67) before becoming a doctoral candidate at the University of California. Because of her political opinions, despite an excellent record as an instructor at the university’s Los Angeles campus, the California Board of Regents in 1970 refused to renew her position as professor in philosophy.

Read MoreDespite this in 1991, Davis became a professor in the field of the history of consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz. In 1995, amid much controversy, she was appointed a presidential chair. An advocate for black prisoners in the 60s and 70s, she was close with George Jackson, who was one of the Soledad Brothers. His brother Jonathan was one of four killed in an abortive/kidnapping attempt from the Hall of Justice in Marin county, California on August 7, 1970. Davis was suspected of being complicit and became one of the FBIs most wanted criminals. She was arrested in New York City in October 1970, and returned to California to face chariges of kidnapping, murder, and conspiracy; She was later aquited of all charges by an all-white jury. She published an autobiography in 1974 and later in 1980 she ran for US vice president on an unsuccessful Communist Party ticket.

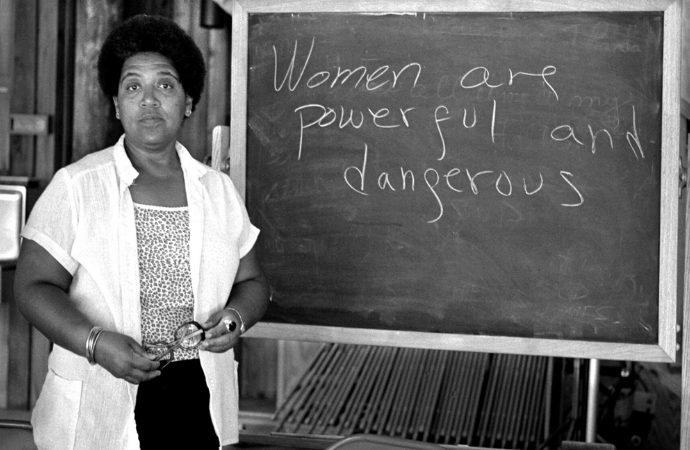

Audre Lorde (1934-1992)

Activist, Poet, Educator

A self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” Audre Lorde dedicated both her life and her creative talent to confronting and addressing injustices of racism, sexism, classism, and homophobia. Lorde was born in New York City to West Indian immigrant parents. She attended Catholic schools before graduating from Hunter High School and published her first poem in Seventeen magazine while still a student there.

Read MoreOf her poetic beginnings Lorde commented in Black Women Writers: “I used to speak in poetry. I would read poems, and I would memorize them. People would say, well what do you think, Audre. What happened to you yesterday? And I would recite a poem and somewhere in that poem would be a line or a feeling I would be sharing. In other words, I literally communicated through poetry. And when I couldn’t find the poems to express the things I was feeling, that’s what started me writing poetry, and that was when I was twelve or thirteen.”

Lorde earned her BA from Hunter College and MLS from Columbia University. She was a librarian in the New York public schools throughout the 1960s. She had two children with her husband, Edwin Rollins, a white, gay man, before they divorced in 1970. In 1972, Lorde met her long-time partner, Frances Clayton. She also began teaching as poet-in-residence at Tougaloo College. Her experiences with teaching and pedagogy—as well as her place as a Black, queer woman in white academia—went on to inform her life and work. Indeed, Lorde’s contributions to feminist theory, critical race studies, and queer theory intertwine her personal experiences with broader political aims. Lorde articulated early on the intersections of race, class, and gender in canonical essays such as “The Master’s Tools Will Not Dismantle the Master’s House.”

Marsha P. Johnson (1945 –1992)

Activist, Sex Worker, Community Organizer

Marsha “Pay it No Mind” Johnson (1945-1992) was a Black trans woman who was a force behind the Stonewall Riots and surrounding activism that sparked a new phase of the LGBTQ+ movement in 1969. Along with Sylvia Rivera, she established the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970–a group committed to supporting transgender youth experiencing homelessness in New York City.

Read MoreMarsha P. Johnson was tragically murdered on July 6, 1992 at the age of forty-six. Her case was originally closed by the NYPD as an alleged suicide, but transgender activist Mariah Lopez fought for it to be reopened for investigation in 2012. Marsha P. Johnson is now one of the most venerated icons in LGBTQ+ history, has been celebrated in a series of books, documentaries, and films. Her actions and words continue to inspire trans activism and resistance, and will continue to do so well into the future.

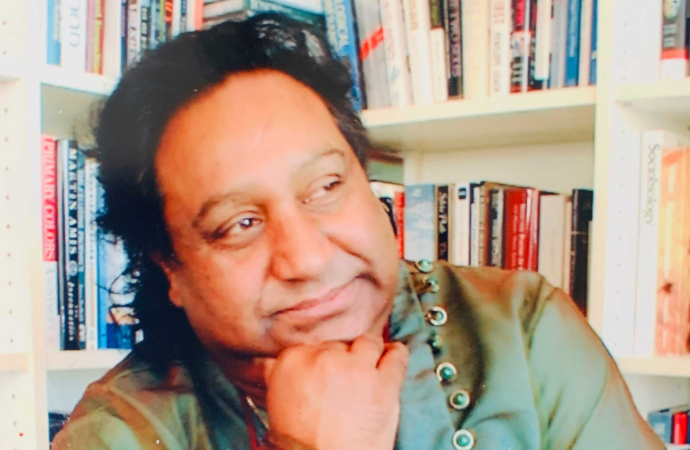

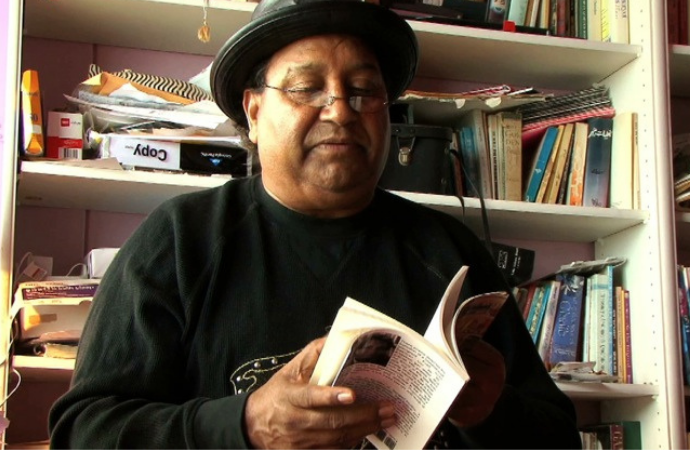

Ifti Nasim (1946-2011)

Activist, Poet,

Ifti Nasim was likely the first openly gay poet to originate from Pakistan. In his early 20’s, he emigrated to the U.S. to escape persecution for his sexual orientation. He became known locally for establishing Sangat, an organization to support LGBT South-Asian youth, and internationally for publishing Narman, a poetry collection deemed to be the first open expression of homosexual themes written in Urdu. A long-term resident of Chicago, Nasim was inducted into the city’s Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame in 1996 but never became a household name beyond the local accolade.

Read MoreNevertheless, as a trailblazing, flamboyant figurehead who courageously forged a path for himself rather than concede to the expectations surrounding him, Nasim deserves greater recognition and honor for his work. In particular, Nasim should be remembered for his significant role in establishing safe spaces for the South Asian LGBTQ community. He displayed that they could lead truthful and happy lives and worked to build institutions that would allow people like himself to adjust and thrive in the world.

Ifti Nasim was born on September 15, 1946, in Faisalabad, Pakistan (then called Lyallpur), shortly before its independence. Nasim learnt Kathak (one of the eight major forms of Indian classical dance) and danced privately amongst close friends. He also started learning and writing poetry, studying all the classic works of Urdu and Punjabi (Indo-Aryan language native to Pakistan and India) poets; according to Nasim, writing poetry while in Pakistan was a huge source of catharsis for him. At age sixteen, though, Nasim was reading a politically charged poem of his at a protest against martial law when a soldier entered the room and shot him in the leg. He was spared getting hit by any more bullets, but Nasim wrapped his own leg and wobbled home, not telling anyone in his family of the incident. The next day, his sister discovered blood and Nasim’s infected wound. The poet was subsequently treated but bedridden for six months, ruining his potentially promising career in classical Kathak dance.

As he matured into his later teenage years, Nasim realized that he was still attracted to men, and anticipating that his family would try to marry him off to a girl, felt he could no longer stay in Pakistan. Nasim’s ultimate decision to flee his homeland was, therefore, one made out of necessity. At the age of 21, inspired in part by an article in Life magazine that Nasim recalled describing the U.S. as “the place for gays to be in,” Nasim immigrated from Pakistan to the States, convincing his father in the process that it was just going to be a three-month tour around America. But of course, after Nasim arrived in America, he stayed for good.

Nasim first landed in New York City, where he found a YMCA on 42nd street at which to stay. After getting his bearings, Nasim enrolled at Wayne State University in Detroit and continued writing and working to help bring more of his family over to the States. Several of his siblings later followed him to the U.S., and Nasim himself was eventually naturalized as a U.S. citizen. In 1974, Nasim moved to Chicago, where he would spend the majority of the rest of his life. There, he started exploring the thriving gay disco scene. Though there may have been many a good time had, it was, of course, still the 1970’s in the U.S. of A., so Nasim was also exposed to rampant homophobia, spurring him to join the growing gay liberation movement. It is around this time that Nasim also began to experiment with his style. He soon became known for his ostentatious getups that often involved fur coats, leather pants, flashy jewelry, and a “pimp” hat.

Nasim was also a regular columnist for Weekly Pakistan News, writing compendious columns that unveiled hypocrisies behind some of society’s self-ordained “pious and decent” members. Simultaneously, Nasim started his own successful radio talk show, which he also hosted, and served as president of the South Asian Performing Arts Council of America. Perhaps most important to his legacy, though, Nasim helped found Sangat (Sanskrit for ‘togetherness”) in 1986, one of the earliest South Asian LGBT organizations in the U.S. The organization provided education and support for queer-identifying South Asians in the region and allowed Nasim—no stranger to gay ostracization—to give back to Chicago’s queer community. For such groundbreaking and impactful work, Nasim was inducted into the Chicago LGBT Hall Of Fame in 1996.

Despite the setback, Narman managed to get passed around, and its frankness inspired a younger generation of Pakistani poets to write “honest poetry,” a new genre for the country that became known as “Narmani Poetry.” With regards to “Narmani Poetry,” Nasim reflected: “But the young people, when they read this poetry, that was revelation for them that somebody can write like that too. So they become enamored with this poetry, and they start writing about true feeling, whether it was toward the sex…before that, our object of love was androgynous, you know, you cannot call him male or female, now they started calling whatever.” Essentially sparking a literary movement, Nasim’s Narman has since been distributed around the world, including in England, Norway, Sweden, and Germany.

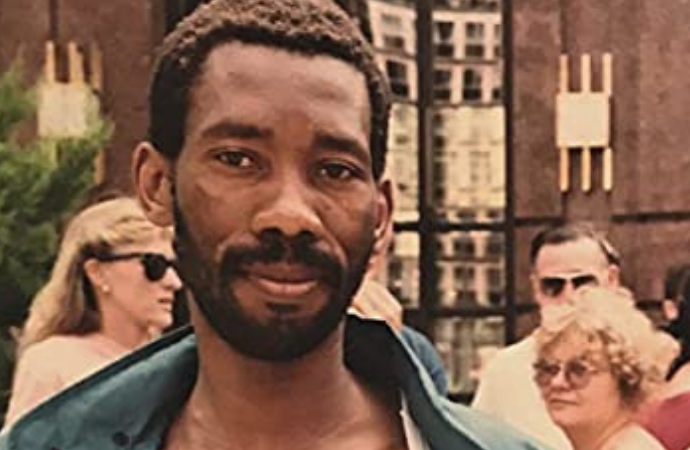

Simon Nkoli (1957-1998)

Activist

Simon Nkoli was a South African anti-apartheid, gay rights and AIDS activist. He is recognized as the founder of South Africa’s black gay movement. Nkoli was born in Soweto. At a young age, he was sent to live on a farm with his grandparents to avoid apartheid. He spent any spare moment in the classroom. Eventually his thirst for education led him to attend school full-time. At 18, Nkoli came out to his mother.

Read MoreShe sent him to a priest to be “argued” out of it. After this and further attempts by psychologists and doctors proved unsuccessful, Nkoli’s mother allowed her son to move in with his boyfriend.As an activist in the 1970s, he was arrested in the student uprisings against apartheid. In 1979, he joined the Congress of South African Students and the United Democratic Front (UDF).In 1983, Nkoli—frustrated that most gay venues were in districts reserved for whites—joined the Gay Association of South Africa (GASA), a predominantly white gay organization. After realizing that GASA would not relocate their social activities outside of whites-only facilities, Nkoli founded the Saturday Group, South Africa’s first regional gay black organization.

For opposing apartheid, Nkoli and other UDF members were charged with treason. While awaiting sentencing, he came out to other UDF leaders, prompting them to recognize homophobia as oppression. In 1988, he and his co-defendants were acquitted. After his release, Nkoli cofounded the Gay and Lesbian Organisation of Witwatersrand (GLOW), the first national black LGBT organization in South Africa.

In the 1990s, Nkoli worked with Nelson Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) to end apartheid. His visibility in the anti-apartheid movement and his association with Mandela helped the gay movement gain support from the ANC. In 1996, South Africa became the first nation to include sexual orientation protection in its constitution. Nkoli was one of the first South Africans to publicly disclose his HIV status. He cofounded the Township AIDS Project and the Gay Men’s Health Forum. In 1998, he died from AIDS-related complications. South Africa’s 1999 Gay Pride March was dedicated to Nkoli’s accomplishments.

William Meezan (1947-2016)

Social Worker

Dr. William (Bill) Meezan retired as the Mary Ann Quaranta Chair in Social Justice for Children and Distinguished Professor at the Fordham University in June of 2014. Prior to that appointment he was Director of Policy and Research at Children’s Rights. Before returning to New York, he was Professor and Dean of the College of Social Work at Ohio State University.

Read MoreHe has also served as the Marion Elizabeth Blue Professor of Children and Families at the University of Michigan and the John Milner Professor of Child Welfare at the University of Southern California. He began his academic career at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Jane Addams College of Social Work, where he rose through the academic ranks, attaining tenure in 1981 and the rank of full professor in 1986. He holds BA from the University of Vermont, his MSW from Florida State University, and his doctorate from Columbia University.

In 1984-85, Dr. Meezan served as a Congressional Science Fellow sponsored by the Society for Research in Child Development, while in 1993-1994 he was a Senior Fulbright Scholar in the Baltic States, where he helped organize the first schools of social work in Lithuania and Latvia. In 1997 he received an honorary degree from the Higher School of Social Work and Social Pedagogics “Attistiba” in Riga for his contribution to the development of social work education in the Latvian Republic, and in 2005 he was inducted into the Columbia University School of Social Work’s Alumni Hall of Fame. More recently, he has been named a Social Work Pioneer by the National Association of Social Work; he was awarded an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from the University of Vermont in May of 2013.

Dr. Meezan is the recipient of the Society for Social Work Research’s Outstanding Research Award (2000), and the Pro Humanitate Literary Award/2009 Herbert A. Raskin Child Welfare Article Award from the Center for Child Welfare Policy of the North American Resource Center for Child Welfare. He has written extensively along the entire continuum of child welfare services, including over numerous articles and chapters in peer reviewed journals and anthologies. He has co-authored four books and co-edited six other volumes. His most recent interests include issues of systems change in child welfare, mission drift in child welfare, the development of children raised by lesbian and gay parents, and research methodologies appropriate for the use with LGBT populations.

Dr. Meezan has been a consultant to numerous social agencies, foundations, schools of social work, and national organizations, and has served on the Boards of the Society for Social Work Research (Secretary and Treasurer), the Institute for the Advancement of Social Work Research (President), the ANSWER Coalition, and the Group for the Advancement of Doctoral Education in Social Work (Secretary), as well as a number of social agencies concerned with children’s mental health and the containment of the AIDS pandemic. He has also served as the Chair of the National Publications Committee of the National Association of Social of Social Workers.

Sylvia Rivera (1951-2002)

Activist

Sylvia Rivera was a queer, Latina, self-identified drag queen who fought tirelessly for transgender rights, as well as for the rights of gender-nonconforming people. After the Stonewall riots, where she was said to have thrown the first brick, Rivera started S.T.A.R. (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), a group focused on providing shelter and support to queer, homeless youth, with Marsha P. Johnson.

Read MoreShe also fought against the exclusion of transgender people in New York’s Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act. She was an activist even on her deathbed, meeting with the Empire State Pride Agenda about trans inclusion.

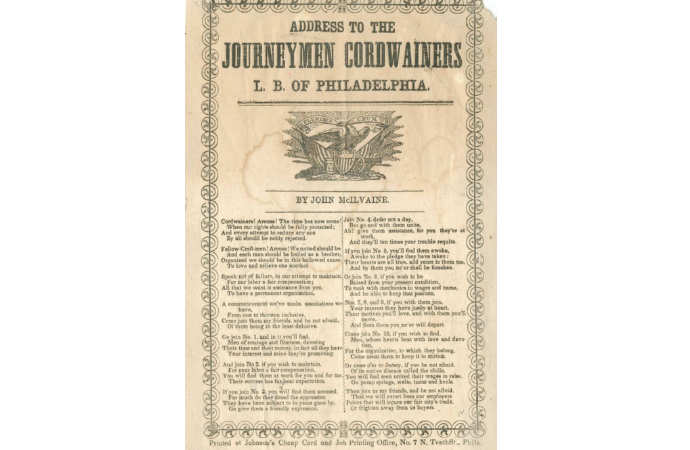

Francis Perkins (1880-1965)

Social Worker, Activist

She was the first woman to be nominated to the United States Cabinet and served as Secretary of Labor from 1933 to 1945. She began her social work career as a volunteer in settlement houses. She quit the New York Consumers League after witnessing the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire and went on to become the executive secretary of the Committee on Safety of the City of New York.

Read MoreShe was able to increase factory investigations, lower women’s workweek hours to 48 hours, and was at the forefront of minimum wage and unemployment insurance regulations while in this role. Her efforts were instrumental in bringing the labor movement into the New Deal coalition, and she established the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Public Works Administration (later the Federal Works Agency), and the labor portion of the National Industrial Recovery Act during her tenure as Secretary of Labor.

She was instrumental in the passage of the Social Security Act, which provided unemployment compensation, pensions, and welfare payments. She helped to establish minimum wage and overtime laws, as well as define the standard 40-hour work week, through the Fair Labor Standards Act. She also founded the United States Conciliation Service, which helped to alleviate union strikes by establishing policy that shaped how the government worked with unions.

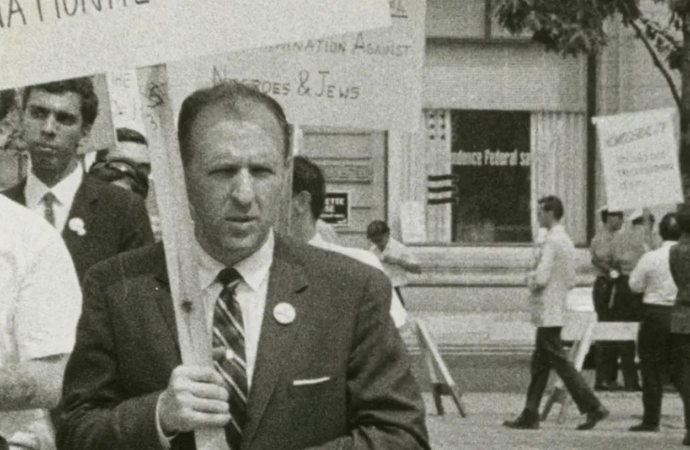

Frank Kameny (1925-2011)

Activist

Institutionalized anti-gay bigotry during the McCarthy-Era drove astronomer Frank Kameny from his job at the U.S. Army Map Service and into the pantheon of modern LGBT activism. He single-handedly took on the U.S. government – using his own name and face in an era when most gay people could not risk being photographed – to petition the Supreme Court in 1961 in a futile attempt to overturn his job dismissal.

Read MoreEffectively unemployable in his chosen field, he struggled in poverty while an aggressive, pro-active, politically-driven crusade – fueled by his uncompromising belief that “Gay is Good” – took shape in his mind. An apostate of the early Homophile Movement, Kameny rejected characterizing homosexuality as a border-line mental illness in order to win sympathy, if not approval, from straight people. Arguing that “gays must not be a mere passive battlefield across which conflicting ‘authorities’ fight their intellectual battles” – and that they should play an active role in determining their own fate – he co-founded an independent chapter of the Mattachine Society in Washington DC to focus on changing laws and challenging institutions whose policies forced people to remain closeted. Along with Barbara Gittings, he led the successful effort to remove homosexuality from the American Psychiatric Association’s list of mental disorders in 1973. A veteran of World War II, Kameny deliberately orchestrated Vietnam War hero Sgt. Leonard Matloyich’s public admission of homosexuality in order to bring the issue of gay people serving openly in the military into the national consciousness.

35 years later he was seated in the front row when President Barack Obama signed the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” into law – ending the battle he had helped to start. Kameny’s tactical instincts – though heretical in his time – foreshadowed political victories which are taken for granted today. In 2009 he received a formal apology from the U.S. government for the original job dismissal that catalyzed his resolve to transform the way gay people were treated in society. His numerous accomplishments have made him one of the most influential LGBT activists in history. He passed away at the age of 86 on October 11, 2011 – “National Coming-Out Day.”

Barbara Gittings (1932-2007)

Activist

In 1948, a high school teacher informed Gittings she had most likely been kept out of the honor society due to “homosexual inclinations.” These opinions followed her through college, and while she did not find issue with the label being applied to her she did not understand why the label of homosesxual was considered “sick or sinful.” In 1956 she joined the Daughters of Bilitis, the first female homophile group in the US that was dedicated to improving the lives of lesbians. She went on to organize the first East Coast chapter in 1958.

Read MoreShe participated in the first gay marches outside the White House and Pentagon with signs that read “sexual preference is irrelevant to federal employment” which can be seen in the Smithsonian today. In 1973 she worked with Frank Kramey to remove homosexual as a mental disorder, that same year she helped to found the National Gay and Lesbain Task Force. At the 1997 NYC pride she was declared the “mother of lesbian and gay liberation”

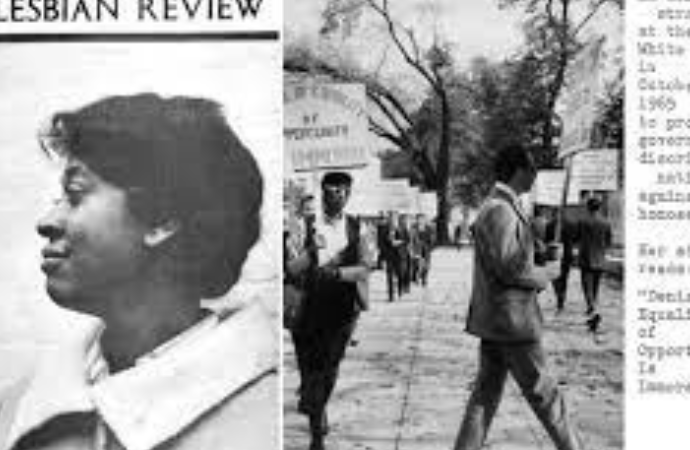

Ernestine Eckstein (1941-1992)

Activist

She is the only Black woman in Kay Lahausen’s famous 1965 photograph of the first gay and lesbian picket line in front of the White House. She carried a sign that read, “Denial of Equality of Opportunity is Immoral.” Her name is Ernestine Eckstein.

A year after the White House picket, Eckstein was the first Black woman to be on the cover of the iconic lesbian magazine, “The Ladder,” published by the lesbian political advocacy group the Daughters of Bilitis.

Read MoreOne of the only sources of historical material on Eckstein’s life and her politics is derived from an eight-page in-depth interview with the then-25-year-old Eckstein, Kay Tobin (Lahausen’s pseudonym), and Barbara Gittings, Philadelphia activist and Lahausen’s longtime partner and one of the founders of Daughters of Bilitis. The interview appears in the June 1966 issue of The Ladder on which a photograph of Eckstein graces the cover.

The print interview is culled from audio tapes of a long interview in 1965 with Eckstein. Those tapes were unearthed by Making Gay History (MGH) podcast executive producer Sara Burningham. Burningham uncovered a digitized copy of the interview among the archived papers of Barbara Gittings at the New York Public Library.

Born in South Bend, Indiana on April 23,1941 as Ernestine Delois Eppenger, one of eight children of Darnell and Cecelia Eppenger, she adopted the name Eckstein to protect herself from backlash in her job and personal life. In “The Ladder” interview, Eckstein said, “I will get in a picket line, but in a different city.” She knew the dangers of being openly lesbian in those years before Stonewall.

After college, in 1963, the 22-year-old Eckstein moved to New York City where she began attending meetings of the New York Mattachine Society, one of the earliest gay rights organizations. Eckstein told Lahausen and Gittings that moving to New York City allowed her to come out as a lesbian to herself and to others. That in turn fueled her nascent gay activism. She says in The Ladder that her sexual identity and orientation had always been hovering in the background of her emotional life, but she had no clear articulation of it prior to moving to New York.

Once there, she blossomed. She said, “This was a kind of blank that had never been filled by anything until after I came to New York… I didn’t know the term gay! And he [a gay male friend from Indiana who was living in New York] explained it to me. Then all of a sudden things began to click… the next thing on the agenda was to find a way of being in the homosexual movement.”

Marcia M. Gallo wrote in “For Love And For Life, LGBTQ People Are Not Going Back” that Eckstein “had experience working with civil rights organizations such as the NAACP as a college student in Indiana before moving to Manhattan in the early 1960s; she joined the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) shortly thereafter. She became vice president of the New York Chapter of DOB in 1964 and for the next four years was an influential leader who urged the group and the movement in general to engage in more direct action efforts.”

Eckstein also participated in the “Annual Reminder” gay and lesbian picket protests outside Independence Hall on July 4th in Philadelphia that were chronicled by Lahausen. At those protests, organized by activist Frank Kameny, Eckstein was frequently one of the only women — and the only Black woman — present.

Ecsktein corresponded with Frank Kameny and in his papers are letters between the two in 1965 and 1966. Eckstein wanted Kameny to speak at DOB headquarters to bolster her position that activism and activist strategies and tactics were essential to progress for the lesbian and gay movement.

An early activist in the Black feminist movement of the 1970s and the organization Black Women Organized for Action (BWOA), Eckstein had also argued in her interview with “The Ladder” for gays and lesbians to embrace the protest actions of the Black Civil Rights movement. She told Gittings and Lahousen, “The homosexual has to call attention to the fact that he’s been unjustly acted upon on. This is what the Negro did. Demonstrations, as far as I’m concerned, are one of the very first steps toward changing society. I would like to see in the homophile movement more people who can think. Movements should be intended, I feel, to erase labels, whether ‘black’ or ‘white’ or ‘homosexual’ or ‘heterosexual’. I’d like to find a way of getting all classes of homosexuals involved together in the movement.”

That Eckstein was a profoundly radical and progressive activist is reflected in both her work with DOB and her work with BWOA. Unfortunately little is known of her work post-BWOA, including the circumstances of her death in 1992. But the archive of photos by Lahousen, the extraordinary interview with her, and the extant papers from BWOA illumine a woman of intense commitment and immense drive for the furtherance of equity for gay and Black people and most especially, Black lesbians.

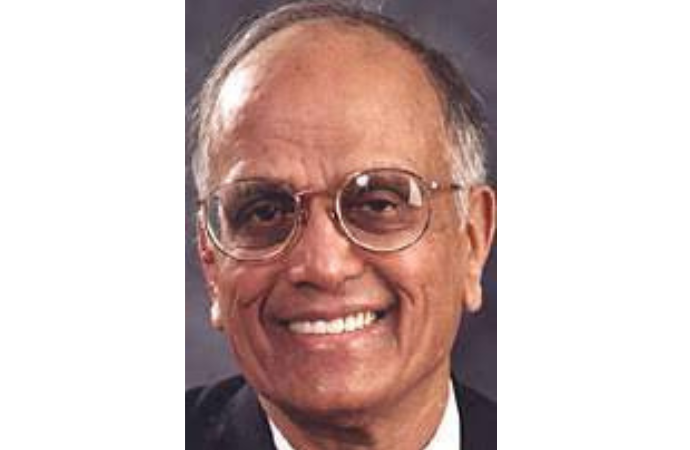

Shanti Khindika (1933- )

Social Worker

Shanti Khindika holds Master’s Degrees in Social Work from both Lucknow University in India and the University of Southern California and holds a PhD from Brandeis University. He was Assistant Dean at St. Louis University’s School of Social Work. In 1973 he became the founding Director of the Kothari Center for Environmental Research in Calcutta, India. He later became Dean of the George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University.

Read MoreHe has held seats on the Council on Social Work Education’s (CSWE) Board of Directors, Commission on Accreditation and House of Delegates, among other CSWE bodies. For NASW he has chaired and been a member of the Publications Committee, International Activities Committee and two professional symposium planning committees He also chaired the accreditation committee of the National Association of Deans and Directors of Social Work. He is the author or editor of more than 40 books, book chapters, journal articles and monographs. He has written extensively on social work education, as well as on international social work, ethnic diversity, and juvenile services. NASW awarded him the President’s Award for Excellence in Education.

Emma Tenayuca (1916-1999)

Activist, Community Organizer

Emma Tenayuca was a Mexican American labor organizer and civil rights activist. She led a wave of strikes by women workers in Texas in the 1930s. During this time, the Great Depression had led to terrible hardship for many Americans. New Deal laws expanded the rights of workers to organize unions and demand better conditions. But it was leaders like Tenayuca who brought people together to fight for changes in their lives. Her actions empowered her community and inspired workers across the country.

Read MoreEmma Tenayuca was born into a large Catholic family in San Antonio on December 21, 1916. She lived with her grandparents as a child. The family traced their roots to Native American and Spanish ancestors in Texas and Mexico. Tenayuca’s grandfather, Francisco Zepeda, passed on a strong sense of Mexican identity and a concern for social justice to his granddaughter. On Sundays, they would often visit the Plaza del Zacate in San Antonio’s Milam Park. They listened to soapbox speakers discuss religion, labor rights, and politics, and kept up to date on the latest news of the Mexican Revolution.

At Brackenridge High School, Tenayuca was a star scholar, a talented athlete, and soon a political activist. In 1933, she decided to join a strike of women workers at the H.W. Finck Cigar Company. She watched police beat up striking workers before being arrested herself. The experience made a deep impression. So did the poverty and desperation brought on by the Great Depression. In her 70s, Tenayuca told an interviewer that the goal of her activism wasn’t a certain ideology or an abstract concept, but simply: “Food! Food.”

After graduation, Tenayuca took a job as an elevator operator at the Gunter Hotel.[2] She collaborated with other female activists to organize women workers across San Antonio. At first, Tenayuca worked with more moderate organizations and unions like the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) and the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU). But she grew frustrated with these groups. She believed that they neglected the most marginalized people in her Tejano community. Her politics became more radical. She organized left-leaning Texas groups into a coalition called the Workers Alliance, and later became affiliated with the Communist Party.

Tenayuca led strikes, walkouts, and protests to respond to issues that particularly affected Mexican Americans. They faced discrimination in the New Deal jobs and aid programs that were supposed to help workers recover from the Depression. The police targeted them for violence and illegal deportations. In San Antonio, the Mexican neighborhoods on the West Side were basically slums: neglected by the city government and suffering from horrible sanitation, housing, and infrastructure.

Tenayuca’s greatest fame came in 1938, when she led a huge strike by pecan shellers in San Antonio, the largest in the city’s history. Pecan production was a large industry in the city. Pecan companies could get away with paying desperate workers just pennies for the dirty, difficult work. This changed on January 31, 1938, when hundreds of pecan shellers walked off their jobs at the Delicious Pecan Company in protest of management’s plan to lower wages even further.

These workers, mostly women, elected Tenayuca their leader. The strike grew to include 12,000 workers and lasted for three months. San Antonio’s mayor sent the police out with tear gas and clubs to break up picket lines and arrest strikers, but they did not back down. Tenayuca’s passionate speeches brought national attention to the strike.

But her ties to the Communist Party also made her a target. Union officials feared that her politics would turn public opinion against the strikers, and they removed her as strike leader. The loss of the official title didn’t stop her. She remained out on the picket lines, giving speeches and writing pamphlets in support of the workers.

The action ended in a compromise, but the pecan shellers saw their jobs replaced by mechanization over the next several years. However, the strike did reverberate into San Antonio’s politics. Former Representative Maury Maverick supported the strikers. In 1939, he launched a campaign for mayor with the support of Mexican American voters. He won, demonstrating the political power of this group.[3]

Meanwhile, Tenayuca continued her political activities, which sometimes proved dangerous. In 1939, police had to hustle her out of the San Antonio Municipal Auditorium via an underground tunnel when angry protestors stormed a Communist Party rally there.[4] Death threats forced her to leave San Antonio soon after.

She returned to her hometown of San Antonio in the late 1960s. Scholars and activists in the Chicano and women’s liberation movements rediscovered her life and work. She was inducted into the San Antonio Women’s Hall of Fame in 1991, and she died in 1999 at the age of 82.

Luisa Moreno ( 1906-1992)

Activist, Journalist, Community Organizer

Luisa Moreno helped form the National Congress of Spanish-Speaking Peoples in 1938, which battled for equal treatment for Latinx workers and against segregation in public areas, schools, and housing. Moreno was a Guatemalan journalist and activist who fought for women’s admission to institutions. In the United States, she campaigned to organize workers in places including New York’s garment sector, New Orleans’ cane workers, San Diego’s tuna packing employees, and Florida’s cigar rollers.

Read MoreShe developed multicultural alliances in these locations to strengthen worker solidarity and educate them about their rights and how to report violations. She went on to become an international spokesperson for the United Cannery Agricultural Packing and Allied Workers of America, the first CIO local to have a majority of Mexican women as members. She was also one of the founding members of the Latina American Federation of Labor, and her 1940 speech, “Caravans of Sorrow,” is still relevant today. She was threatened with deportation in the 1940s since she was a member of the Communist Party at one point, and she left the country willingly in 1950.

Antonia Pantoja (1922-2012)

Activist

Antonia Pantoja was regarded by many in the Puerto Rico Latino community as one of the most important leaders in the United States. She was a charismatic and visionary leader. In 1997 she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation’s highest civilian honor, from President Clinton during a ceremony at the White House.

Read MoreHe praised her work as founder of ASPIRA, an organization that promotes cultural pride, education, leadership training and community service for Latino youth. Pantoja also helped found the National Puerto Rico Forum and Boricua College. “Peace and respect – these are the values that define the work of Antonia Pantoja” Clinton said in presenting the award. “Her contributions to her people and, therefore, our country are unsurpassed,” he added, calling Panjota “the most respected and loved member of the Puerto Rican community.” “The impact of her work and her contributions to our community has had reverberations so profound and so broad that for generations to come, she will continue to be an inspiration for young Puerto Ricans,” declared then NASW Executive Director Josephine Nieves at a reception. She was involved in a variety of community and professional organizations, all working toward the goal of building stronger Puerto Rican and minority communities, including the Ford Foundation, the National Urban Coalition, the Museo del Barrio, the National Association of Social Workers, the Council on Social Work Education, and several other groups and organizations. One of her many friends and colleague wrote that “she never had a conversation with her when she was not addressing, or worrying about, a social concern or an injustice…her work was constant, her mind never rested, and everything she did was steeped in her values and ethics.”

Ronald G Lewis (1941- 2019)

Social Worker

Ronald G. Lewis, DSW, one of North America’s foremost authorities in Native American Social Work and legal Indian subjects, retired from Eastern Michigan University. He was the first American Indian to earn a doctorate in the field from the University of Denver in 1974 and became known as the “father of American Indian Social Work”. Born on the Cherokee community in Talequah, Oklahoma, Lewis went on to hold many important positions in academia, as well as on the front lines of his profession.

Read MoreAlways a political activist, Lewis was at the Wounded Knee stand-off in 1973 and at Alcatraz. He was a Psychiatric Social Worker and developed many mental health programs for American Indians at the Talequah and Claremore Indian Hospitals in Oklahoma and later for the entire state of Oklahoma. As the Director of the Indian Liaison Office of the Fitzsimmon Army Medical Hospital in Denver, he worked with returning Viet Nam Indian Veterans. Lewis trained hospital and medical Personnel about culturally appropriate services for Native American people.

The University of Oklahoma, School of Social Work, was his first academic appointment in 1975. From there Lewis taught social work at many institutions of higher learning including the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Arizona State University, and Saskatchewan Indian federated College in Canada, where he was the Dean of the Social Work Department. In addition, Lewis guest-lectured at many colleges across the United States and Canada.

Well known as a leading expert on Indian Social Problem, Lewis published extensively on Federal Policy in Indian Country, child abuse and neglect, alcoholism and the American Indian, which was a special report to the U.S. Congress in 1980. His work aided in the creation of the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. Landmark legislation concerning culturally appropriate services for Indian people was an important part of Lewis’ work. He made important and frequent contributions on Indian issues at every level, from meetings with U.S. presidents, reports to congress, and the creation of curriculum at universities.